Far Afield recently took part in a four-week residency at the Banff Centre for the Arts and Creativity entitled, Geologic Time, led by Max Andrews and Mariana Cánepa Luna (Latitudes), with guest faculty Sean Lynch.

The residency questioned the temporal scale of conventional artistic and cultural methods, wondering how might a geologic lens affect the way we approach these practices? Such a question ignited many of my own thoughts, which have been preoccupied with a time capsule I came across in November of 2016. Buried on September 14, 1988, the location of the capsule is marked by an enormous granite boulder taken from a mountain property near Agassiz, British Columbia. The capsule is designated to be unearthed in 2088, but, alas, it has long since been forgotten. Any instructions as to its care, or its importance, seem to have been inadvertently buried along with it. During the residency I focused my energies on the development of a curatorial project inspired by the time capsule, and framed by the thematics of geologic time. The project is anticipated to take place in the fall of 2018, and details will be released in the new year.

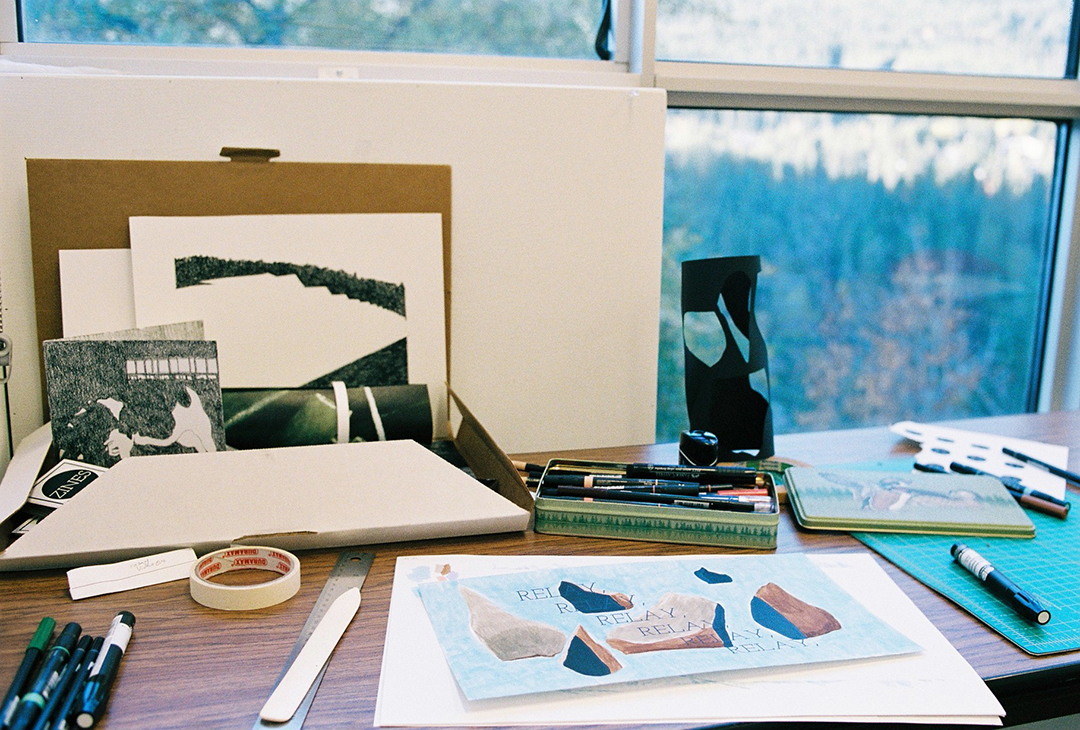

Two components of the residency were highlights of the experience for me, including fieldwork and bookwork. Far from being distinct activities where one would assume fieldwork belongs “outside” and bookwork belongs “inside”, we found ourselves reading in boulder basins and hot springs, while collecting samples and sediments in libraries and studios. I began to loosen some of my assumptions about research, and instead began to think about research activities as stratum that layer one-upon-the-other, grainy sediments that harden into solid, seemingly stable, or coherent states over time; perhaps, over long, long times.

Fieldwork

Some of the fieldwork for the residency included, but was not limited to, visits to: Banff Park Museum; Bankhead; Lake Minnewanka; Stanley Glacier; Upper Banff Hot Springs; and the Whyte Museum.

Select field notes:

Stanley Glacier A Canadian Rockies Public Schools bus pulled into a parking lot in Kootenay National Park, where we clambered out and began the switchbacks up to the receding nose of the Stanley Glacier. Along the way: we viewed the remains of some major forest fires and the resultant new growth; we rested near a bridge over the creek formed by runoff from the glacier; we turned over rocks in the Stanley basin, a boulder field containing Cambrian fossils of soft-bodied marine creatures in the Burgess Shale; we listened to the pikas chirp around us as we ate lunch, and finally caught a glimpse of the very vocal and plump little critter.

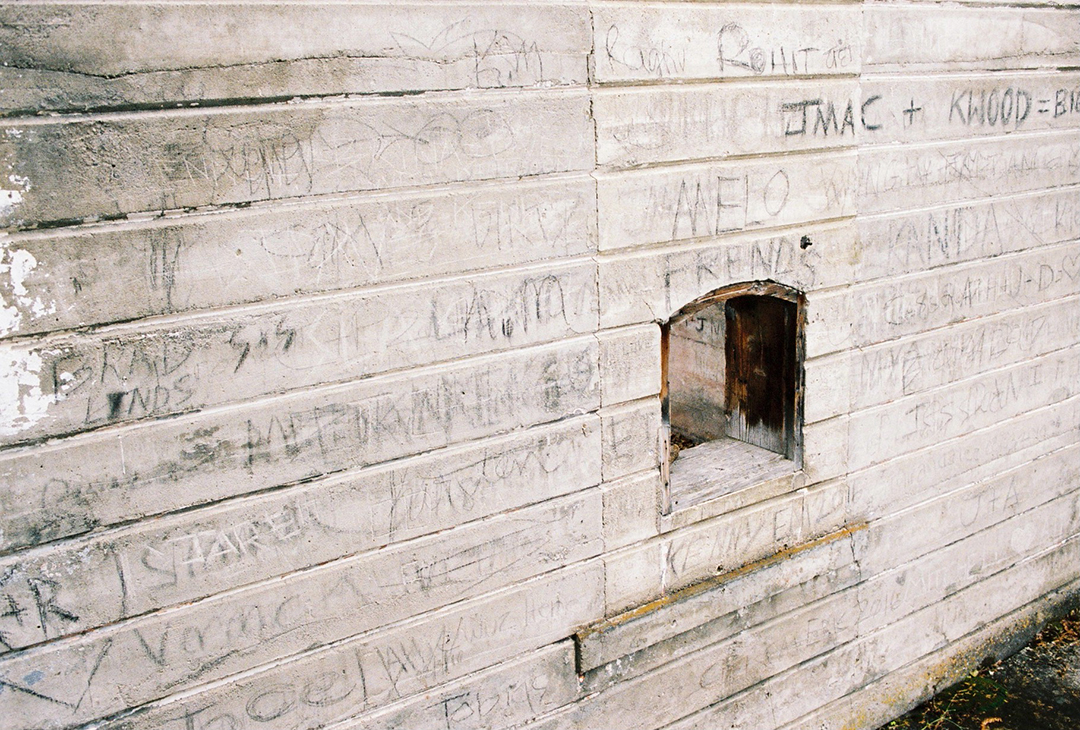

Bankhead The skies clouded over and a veil of mist and light rain encircled us as we began down the steps to Bankhead. Bankhead was once a world-class mining operation (1904-1922), but is now a ghost town that is known locally as the “Twenty-Year Town”. Any building that could be picked up and moved after 1922 was transported either to Banff or Calgary, but the concrete foundations of many of the facilities remain. The Lamp House was once how they accounted for any miners that may have gone missing. Each morning, workers would be given a lamp. Each evening, any lamps that hadn’t been returned to the Lamp House indicated a search party needed to be formed to find the miner who had gone missing. Today, the remains of the Lamp House are covered in graffiti tags, marked onto the walls from the pieces of anthracite coal that can be collected from the pathways and surrounding slack heaps. The graffiti consists predominately of lists of names. No vulgar obscenities, generally, just initials, first names, last names.

Lake Minnewanka Rebecca Belmore's powerful installation Wave Sound rests on the edge of a jutting precipice on the shore of Lake Minnewanka. Wave Sound demands a careful and concentrated form of listening, which amplifies the acoustic qualities of the lake. You have to crouch down onto the rocks to place your ear to the sculpture. You have to make yourself quite small in order to listen to the water well.

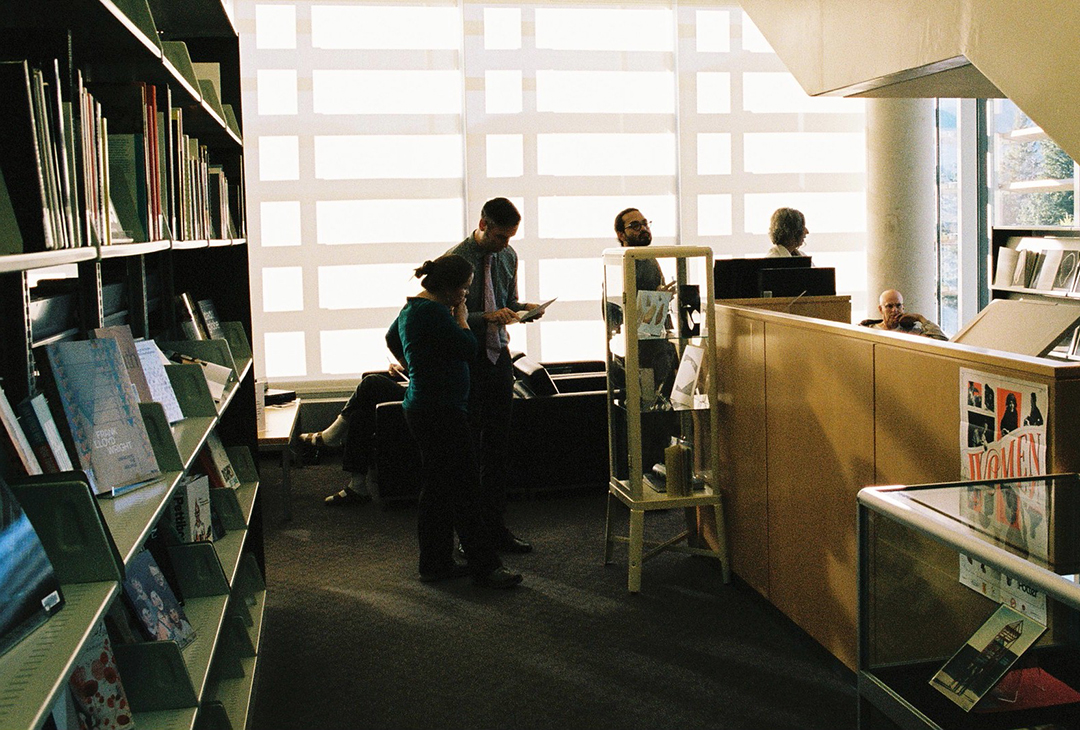

Bookwork

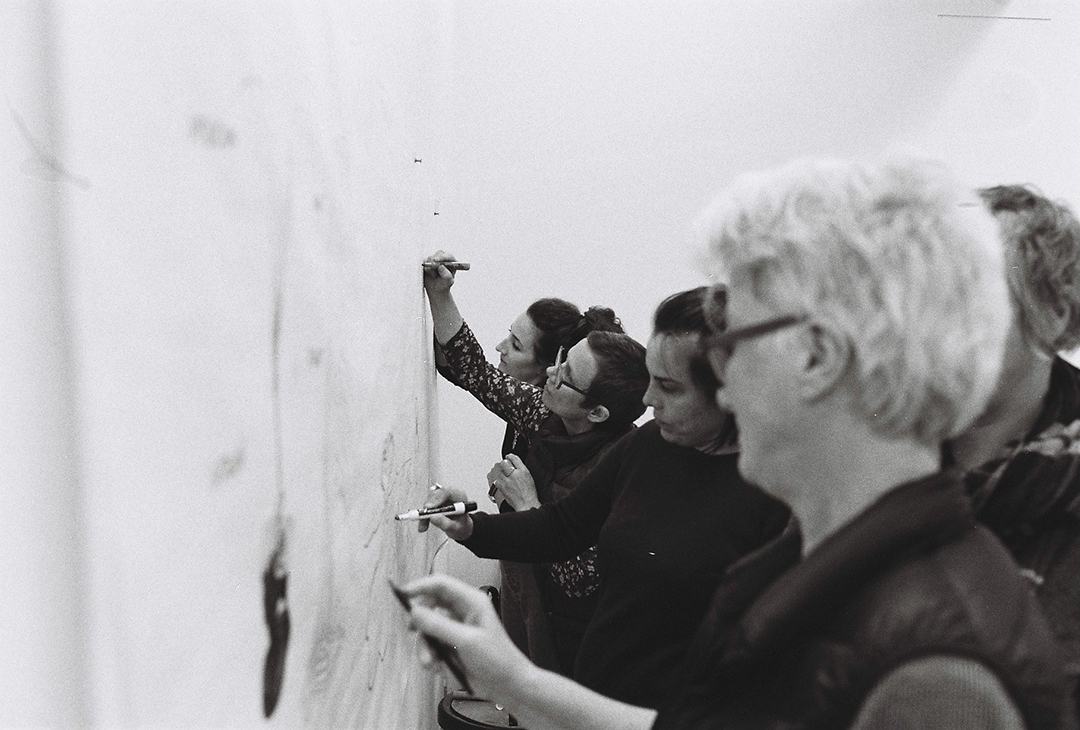

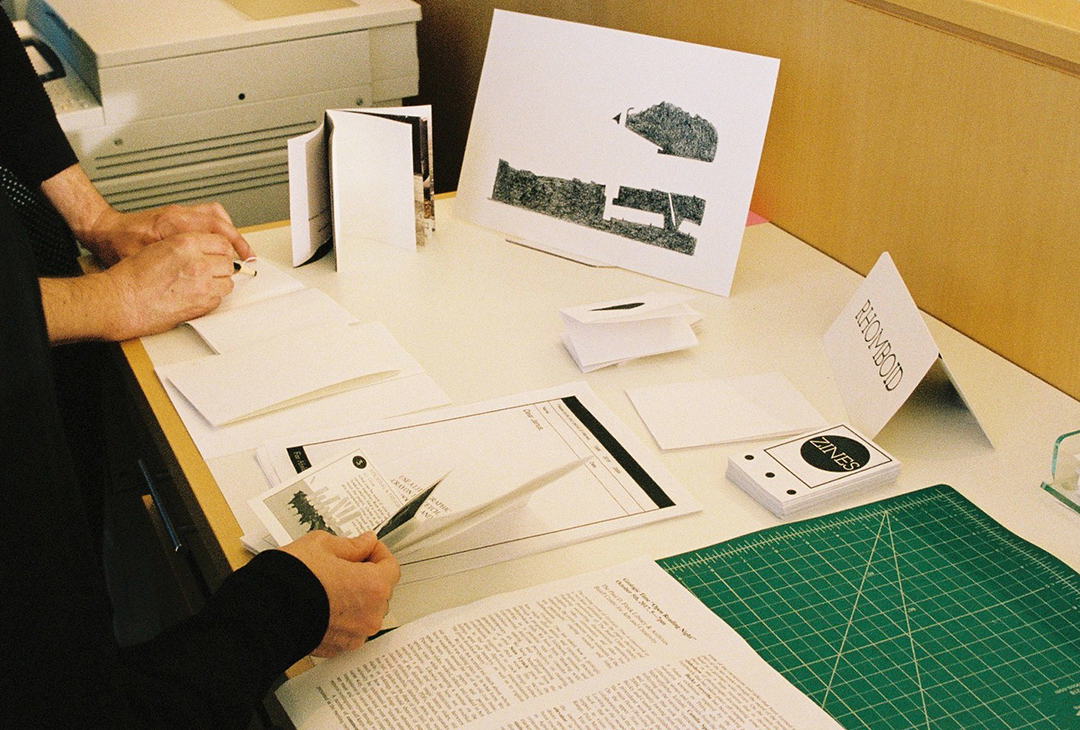

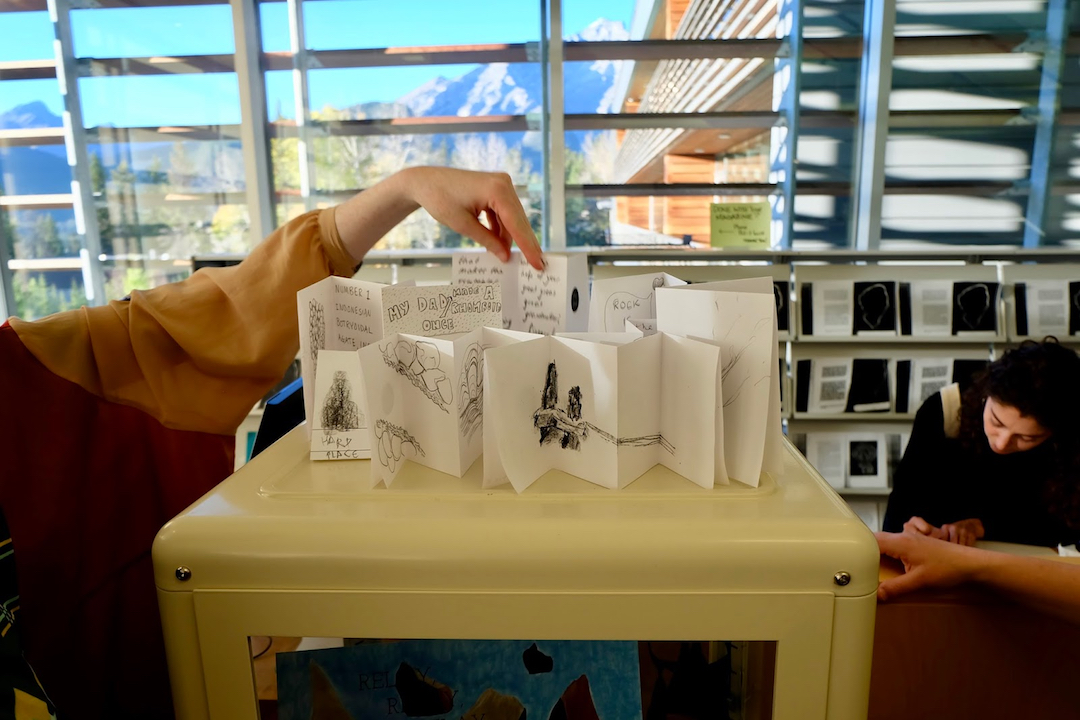

In many ways, “storied matter” became a leitmotif of the residency. Penelope Smart organized and led an informal “geysering” session, which was an opportunity for the group to send our stories, ideas, interests, passions, and research gushing forth. The results of the session were transformed by Smart into a zine, Little Geysers, a copy of which has been included in Far Afield’s library.

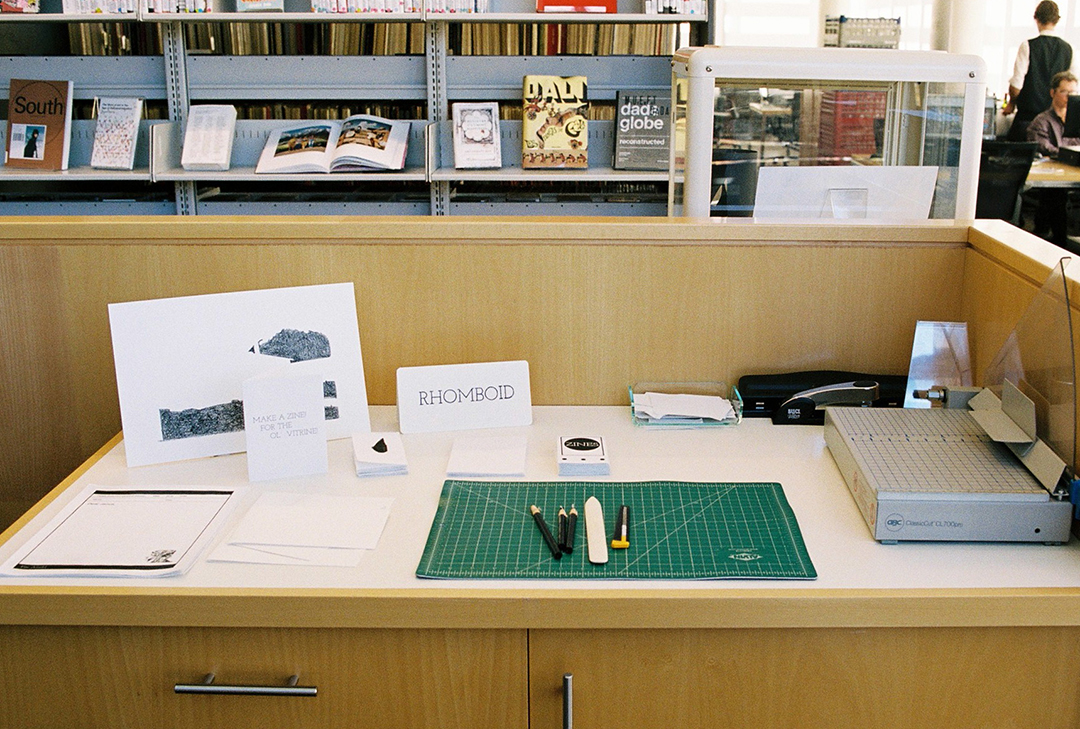

Many other additions to the library were made during the residency, including works by a number of the “geologic timers”. The library now contains a copy of the first eight novellas of Lost Rocks by A Published Event (Justy Phillips & Margaret Woodward), Stone Theatre by Camila Sposati, Receding Agate, and Receding Rhodochrosite by Becky Forsythe and Camila Sposati, in addition to a collection of lithographic crayon zines created by visitors to the closing event of Geologic Time.

My research benefitted tremendously from the sage guidance of faculty (Max, Mariana, Sean), and from the diverse expertise of my colleagues and new friends: Justy Phillips & Margaret Woodward (A Published Event) (Hobart); Semâ Bekirovic (Amsterdam); Becky Forsythe (Reykjavik); Chloe Hodge (London); Shane Krepakevich (Toronto); Caroline Loewen (Calgary); Penelope Smart (St. John’s); Camila Sposati (São Paulo). Many thanks.

I would also like to acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country.