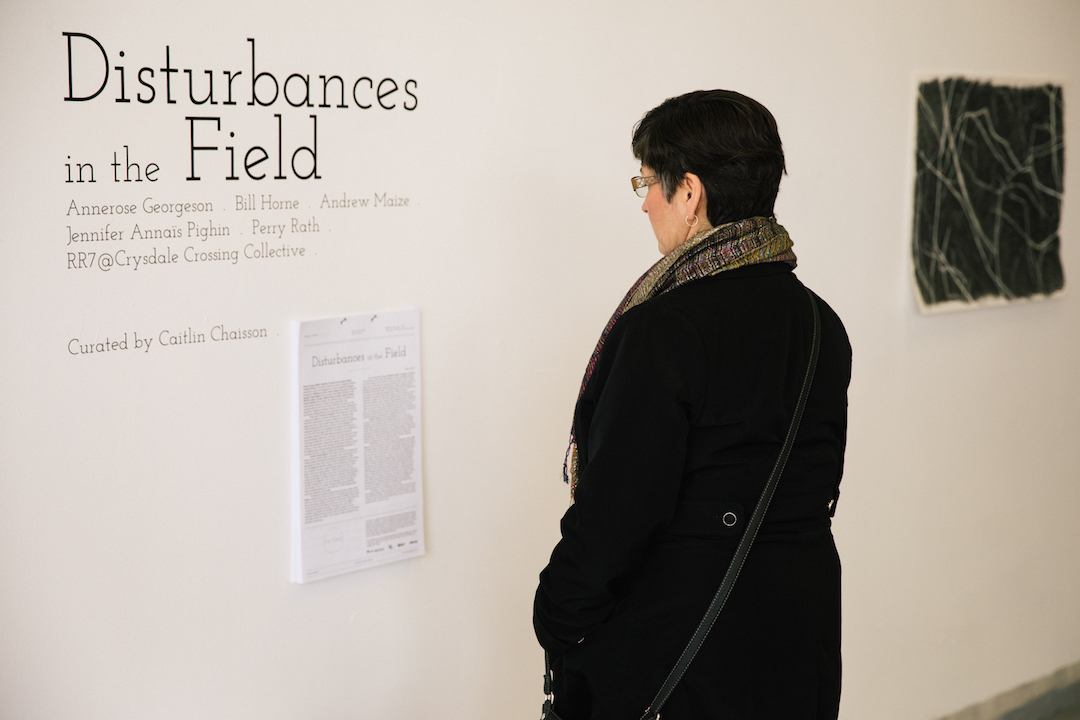

Disturbances in the Field

Prince George | Lheidli T'enneh Territory.

Opening reception Friday, May 12th, 7 pm - 10 pm. Exhibition open to the public May 13th - May 27th, Wednesdays to Saturdays from 2 pm - 7 pm or by appointment. Omineca Arts Centre, 1119 3rd Avenue, Prince George.

Featuring new and experimental works by:

Annerose Georgeson, Bill Horne, Andrew Maize, Jennifer Annaïs Pighin, Perry Rath and the RR7@Crysdale Crossing Collective (Karen Kellett, Judyta Frodyma, Joanna Smythe).

Curated by Caitlin Chaisson, presented by Far Afield.

Curatorial Statement

Download the curatorial statement here.

Prince George, British Columbia | Occupied and unceded Lheidli T’enneh Territory- Far Afield is pleased to present its inaugural exhibition, Disturbances in the Field, featuring new works by Annerose Georgeson (Vanderhoof), Bill Horne (Wells), Andrew Maize (Musquodoboit Harbour), Jennifer Annaïs Pighin (Prince George), Perry Rath (Smithers) and the RR7@Crysdale Crossing Collective (Karen Kellett, Judyta Frodyma, Joanna Smythe) (Prince George). The exhibition aims to complicate our understanding of land-use in Canada, using material and visual experimentation as tools for new modes of thinking. The artists cross the disciplinary boundaries of drawing, sculpture, mixed media, multimedia and performance, eliciting alternative and compelling ways to relate to the land.

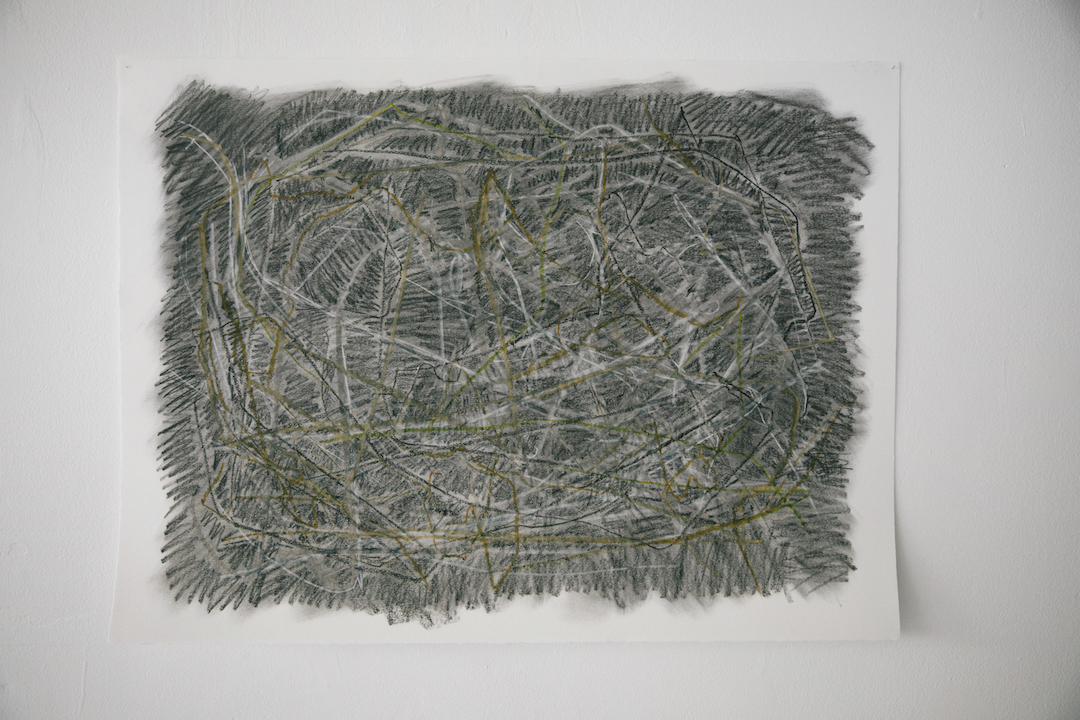

In the work of Annerose Georgeson, the hay that grows on her farm is taken up as fodder for a dedicated drawing practice. Through careful observation in the haylands, Georgeson renders the lines formed by the supple grasses into a script. Despite being carefully recorded, the illegibility of the translation from the field into a version of cursive highlights the inadequacies that exist in any straightforward reading of the landscape. In Loose Hay (2017) and Bagged Hay (2017), Georgeson’s use of abstraction is nevertheless sensitive to the subtle differences between bounded and unbounded spatial configurations. The lines in Loose Hay approach the edge of the page as though they are poised to strike off on their own trajectories, whereas the mark-making in Bagged Hay suggests a slow and gradual circling-in. In all of these works, Georgeson’s approach to drawing occupies the ambiguous space between reading and understanding, prompting us to re-evaluate the ways in which we interpret the landscape.

Jennifer Annaïs Pighin’s Native Status Cards (2017) challenge the desire to mark or label the natural environment, with an attentiveness to the colonial narrative that frequently underpins those designations. Pighin appropriates her Status Card, a form of federal identification under the Indian Act, to highlight the absurdities inherent to this classification of Indigenous lives. Mounted to the wall, a small cardholder displays five Status Cards: Black Cottonwood, Sockeye Salmon, Grizzly Bear, Devil’s Club and Caribou. In keeping with official Status Cards, the identification names the portrait of each figure, but Pighin subverts the underlying colonial imperative through her own adaptations. Native Status Cards presents each inhabitant with their “Family Name” in the Carrier language, their “Given Name” in Latin and their “Alias” in English. Through imitation and modification, Pighin’s deliberate alterations confront the way in which language shapes and encodes eligibility and privilege.

Troubling the boundaries between human and natural realms, Perry Rath’s sculptural work Field Gaze (2017) is a crystalline geometric structure built out of wood salvaged from scrap piles around the Bulkley Valley. Inside the structure hangs a pendant in the shape of a human head, filled with a ball of suet and seed. Part bird-feeder, part scarecrow, the work suggests a complicated relationship with nature. Throughout the course of the exhibition, the sculpture will undertake a migratory pattern of its own, appearing in different rural and urban locations around the city. Left outdoors for periods of time, the sculpture will eventually weather, bearing the traces and marks of its journey.

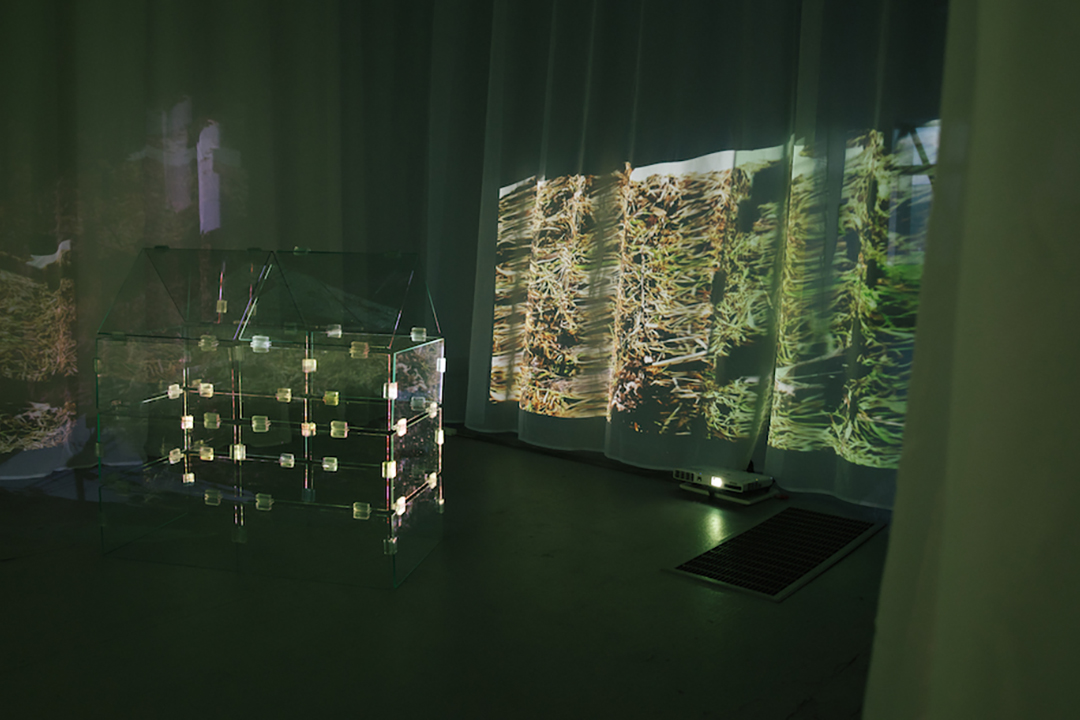

From a more fixed vantage, RR7@Crysdale Crossing’s multimedia work Glosshouse (2017) refers specifically to a piece of farmland owned by one of the members of the collective. Glosshouse projects a video of a dead eagle lying in a field that is in a seasonal transition from winter to spring. The projection is shone through a glass greenhouse, filtering light through the architectural model like a prism. As the light disperses, the work fractures the way nature is viewed through particular lenses. While Glosshouse interrogates the projected image of the landscape, Get the Glyphosate (2017) physically re-locates some of the farm’s earthy material onto the sidewalk outside the exhibition space. Wooden cabbage transplant boxes are filled with Fraser silt loam (a type of soil), which sprouts couch and quack grass. On an otherwise concrete horizon, these small grassy plots punctuate the urban space. The temporary intervention in the city-centre merits a consideration of the debates between what we consider to be natural or artificial, and how our cultural perceptions and experiences complicate these divisions.

Andrew Maize’s process-based endurance work, nations are narrations (2017), unfolds slowly throughout the course of the exhibition. Boarding a cross-continental train in Nova Scotia that is bound for Prince George, Maize’s artwork stems from his travels across the expanse of the country. Maize explores the narrative role of image-making in relation to the construction of national mythologies, particularly the colonialist antecedents that shaped the Canadian Pacific Railroad. Disrupting the benign and altruistic façade of this historic institution, Maize will stitch together a number of counter-narratives throughout his journey.

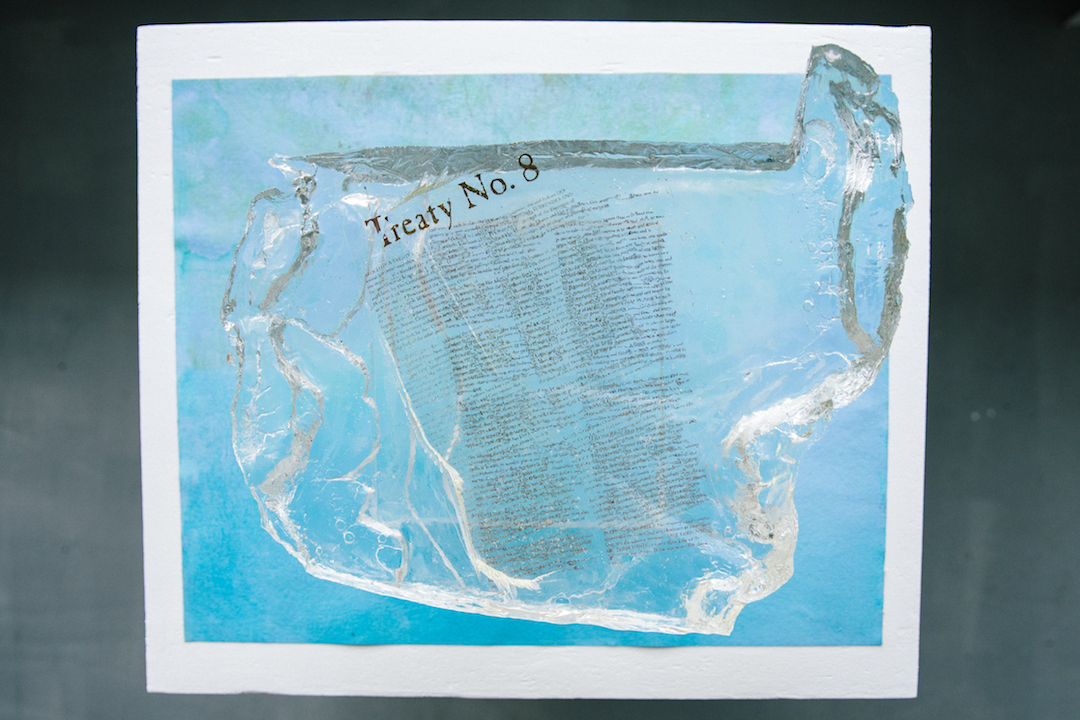

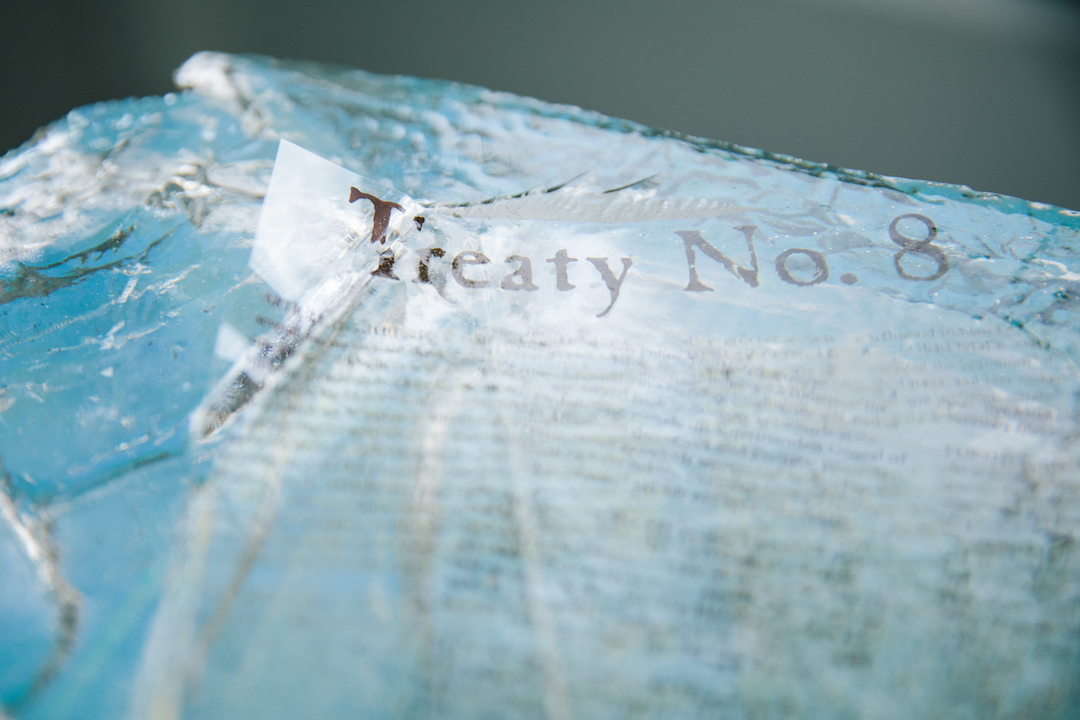

While Maize’s work covers an engrossing geographic expanse, Bill Horne has been emboldened by specific developments in the Peace Region of Northern British Columbia. Horne’s work pointedly addresses BC Hydro’s Site C Dam and the activisms that have challenged the controversial project since the early days of construction. Reservoir (2017) is a sculptural work that encases a silkscreened copy of Treaty 8 in resin. The semi-transparent material takes on the quality and appearance of flood waters, obscuring the ability to read the two-page document. In light of the dam’s encroaching developments, this submersion viscerally and symbolically points to the significant cultural and legal losses faced by Treaty 8. Stakes in the Peace (2017) addresses another aspect of the ramifications of the mega-industry project. Imitating the yard of the Boon family farm, one of the major and continuing sites of resistance to the dam, a terracotta bed contains a field of yellow stakes screen-printed with the hashtags: #nositec, #keepthepeace, #keepthepromise. Through miniaturization, replication and printing processes, the strategies of circulation, distribution and multiples allow protest and opposition to be brought into new contexts.

Disturbances in the Field brings together artists and artworks whose wide-ranging influences liberally transform our assumptions about land and about situated knowledges. The disruption posed by the exhibition is meant to inspire a critical turn towards thinking about occupancy of the natural and cultural world in a myriad of ways.

This exhibition has been generously supported by the British Columbia Arts Council, Living Labs at Emily Carr University of Art and Design, Two Rivers Gallery and Omineca Arts Centre. Disturbances in the Field respectfully acknowledges its presence on occupied and unceded Lheidli T’enneh Territory.

Public Events

All listed events are free and open to the public. Details on the programming can be found on the events page.

Download the events poster here.

Download the exhibition poster here.

Local artisan Lena Trombly's Alien Antler keychain. 2016. Purchased at the Prince George Farmers’ Market. Photo by Denis Gutiérrez-Ogrinc.